India’s climate performance ranks declined

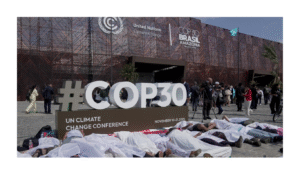

India has dropped from 10th to 23rd place in the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) 2026, moving from the high performers’ group to the medium performing countries category. This index, which evaluates the climate performance of various nations, was published by German watch, the New Climate Institute, and the Climate Action Network during the ongoing UN climate conference (COP30) in Belém.

India has consistently ranked among the top 10 nations in the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) for six consecutive years since 2019. This index evaluates the climate performance of 63 countries and the European Union across four key categories: greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), renewable energy, energy consumption, and climate policy. In the most recent edition, India achieved a medium rating in GHG emissions, climate policy, and energy consumption, while receiving a low rating in renewable energy.

The CCPI outlines various policy measures implemented by India in relation to climate change. It emphasizes that India is demonstrating a long-term commitment through a formal climate strategy, ambitious renewable energy objectives, and established efficiency programs, which include appliance labeling under the Bureau of Energy Efficiency and the Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) mechanism. Furthermore, the report underscores recent policy advancements, such as the green finance taxonomy and the framework for a national carbon market.

It highlights that the implementation of renewable energy is still growing through auctions and financial instruments, bolstered by decreasing tariffs and robust participation. Furthermore, India announced that it reached 50% of its installed power capacity from non-fossil sources by 2025, significantly ahead of its 2030 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) goal.

Revision and Funding

Although COP30 was anticipated to place significant emphasis on adaptation, nations continue to be divided on critical issues. The draft document presents three potential strategies for adaptation finance. The first suggests tripling adaptation funding, with target deadlines of 2030 or 2035, and highlights “public sources” for further discussions. The second option acknowledges the necessity to substantially increase adaptation finance but does not provide any specific amount. The third option urges developed nations to at least triple their combined contribution of climate finance for adaptation to developing countries from the levels established in 2025 by the year 2030.

During his address at the Baku High Level Dialogue on Adaptation in Belém on November 20, Yadav emphasized that developing nations will need between $310 billion and $365 billion each year by 2035, whereas the current financial inflows are approximately $26 billion. He mentioned that India has raised its adaptation-related spending by 150% from 2016–17 to 2022–23, yet it still encounters complicated and sluggish processes when trying to access multilateral climate funding. He stressed that adaptation financing should be provided as grants instead of loans that exacerbate debt levels.

Indian analysts monitoring the discussions indicated that advancements in adaptation are progressing at a slow pace. Vaibhav Chaturvedi from the think tank Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) pointed out that the Global Goal on Adaptation is lacking political drive among negotiating groups and that ambiguous public finance regulations could hinder domestic planning.

Climate finance continues to be a contentious issue

The call for climate finance remains India’s most persistent message at COP30. Yadav has consistently emphasized that developed nations must fulfill their commitments under Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement, which mandates the provision of public, concessional, and predictable financial support. The draft text reflects this assertion. It advocates for the implementation of Article 9, reaffirms the financial duties of developed nations, and highlights that global financing for developing countries must increase to $1.3 trillion annually by 2035.

At COP29, the parties concluded the NCQG, which stipulates a transfer of $300 billion from developed to developing nations by 2035. Nevertheless, several developing countries expressed concerns in Baku and subsequently regarding the manner in which the consensus was achieved. They have been reminding the global community of Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement, which articulates: “Developed country Parties shall provide financial resources to assist developing country Parties with respect to both mitigation and adaptation, in continuation of their existing obligations under the Convention.”

Singh stated that the draft text is significantly dependent on private financing and loans from multilateral development banks, yet it fails to guarantee that developed nations fulfill their legal obligations regarding public finance. He also remarked that the suggestion to triple adaptation finance loses credibility when it merges grants with concessional loans. Singh indicated that this strategy could exacerbate the debt burden faced by vulnerable communities. Additionally, he criticized the draft’s terminology concerning fossil fuels, pointing out that the mention of phasing out “inefficient” subsidies creates loopholes instead of promoting a comprehensive and fair phase-out.

The forthcoming stage of negotiations will ascertain whether the outcome of COP30 embodies the principles emphasized by India and other developing nations throughout the week or if it results in a compromise that leaves significant issues unaddressed.

Meanwhile, discussions were temporarily suspended following a fire in the COP30 Blue Zone on November 20, which necessitated the complete evacuation of all delegates and conference attendees. The UNFCCC subsequently confirmed that the fire had been brought under control.

Discrepancies in India’s climate objectives and strategies

India’s revised Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) pledges to achieve 50% of its energy capacity from non-fossil sources by 2030, alongside a 45% decrease in emissions intensity compared to 2005 levels. Nevertheless, experts from the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI) observe that the target for net-zero emissions by 2070 does not correspond with the pathways necessary to limit global warming to 1.5°C. They further emphasize the lack of interim targets for 2035 and 2040, the ambiguity surrounding sector-specific trajectories, and insufficient engagement with civil society and impacted communities.

On the international stage, CCPI points out that India advocates for equity and adheres to the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR), while also spearheading initiatives like the International Solar Alliance. However, it notes that India’s ongoing expansion of fossil fuel usage undermines its credibility in the realm of global climate negotiations.

CCPI concludes that India’s performance could be enhanced by implementing a time-bound reduction of coal usage, ultimately leading to a complete phase-out. This can be accomplished by establishing a date for no new coal projects and determining a peak year for coal consumption, alongside reallocating fossil fuel subsidies to support decentralized, community-owned renewable energy initiatives. Additionally, it advocates for more robust protections for the siting of renewable energy projects, the creation of binding roadmaps at both sectoral and state levels for the phase-out of fossil fuels, and the development of a just transition framework that prioritizes vulnerable communities, smallholders, and local ecosystems.

Nonetheless, India is facing significant challenges. Raghunandan noted that India encounters substantial limitations in reducing coal-based power generation due to the increasing demand for electricity associated with poverty alleviation and development, despite the growth of solar and wind energy capacity. “The limitations consist of insufficient investment, inadequate power evacuation capacity, storage issues, and grid stability. These problems cannot be resolved in the short term.” He further mentioned that the more considerable deficiencies exist in other sectors, such as public transportation, buildings, and waste management, and that India’s NDC 3.0 will indicate whether these sectors are being addressed.

Bibhuti Pati

( Bibhuti Pati is a Senior Bilingual Media Person ( Print and Electronic ) from Odisha who is known for his insightful and serious writings.)

Comments

0 comments